It is a common argument which I hear among developers these days,

regarding SQL locks. Some say that the ‘locks are held for the duration

of the entire transaction’. But others debate that ‘locks will be only

held for the duration of the statement execution’. But who is correct ?

Well both parties are correct up to a certain point. Actually lock durations are depend on the Isolation Levels.

As mentioned in the SQL-99 Standards, there are 4 Transaction Isolation Levels

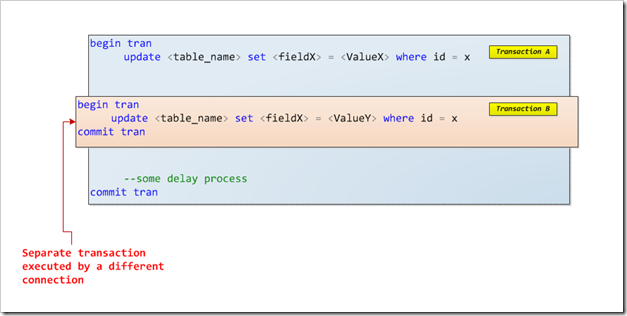

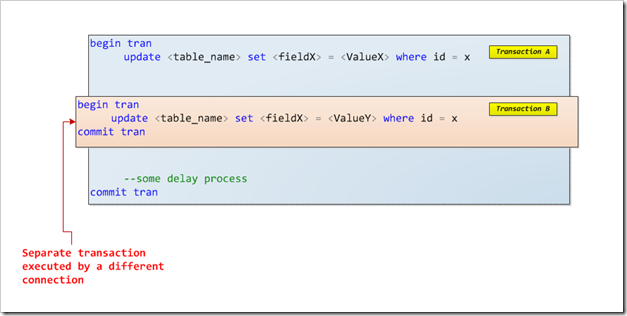

Lost Update – This can take place in two ways. First scenario: it can take place when data that has been updated by one transaction (Transaction A), overwritten by another transaction (Transaction B), before the Transaction A commits or rolls back. (But this type of lost update can never occur in SQL Server** under any transaction isolation level)

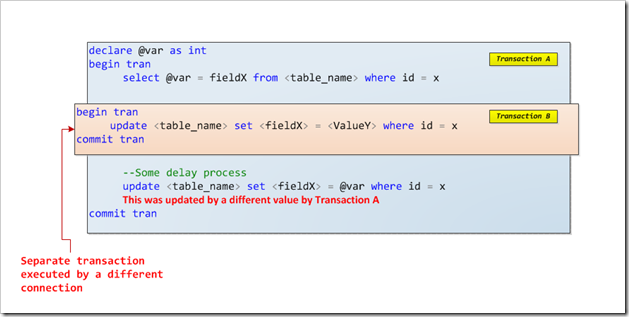

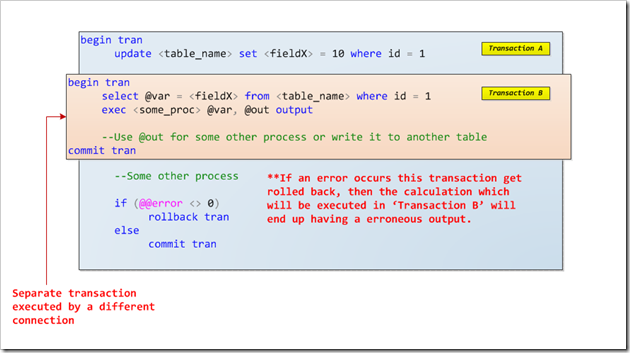

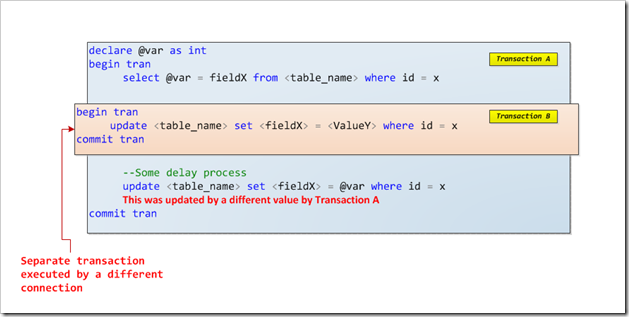

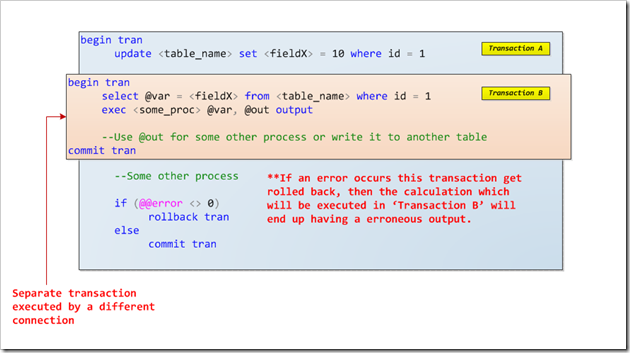

The second scenario is when one transaction (Transaction A) reads a record and retrieve the value into a local variable and that same record will be updated by another transaction (Transaction B). And later Transaction A will update the record using the value in the local variable. In this scenario the update done by Transaction B can be considered as a ‘Lost Update’.

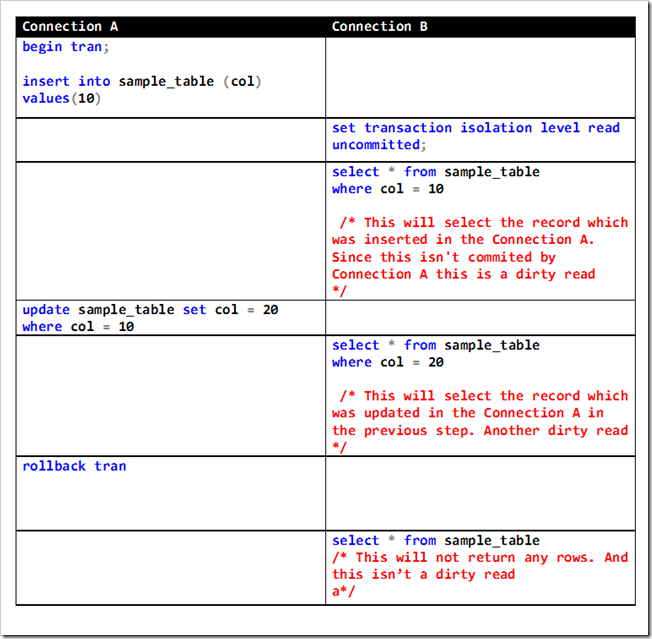

Dirty Read – This is when the data which is changed by one transaction (Uncommitted) is accessed by a different transaction. All isolation levels except for the ‘Read Uncommitted’ are protected against ‘Dirty Reads’.

Non Repeatable Read – This is when a specific set of data which is accessed more than once in one transaction (Transaction A) and between these accesses, it’s being updated or deleted by another transaction (Transaction B). The repeatable read, serializable, and snapshot isolation levels protect a transaction from non-repeatable reads.

Phantom Read – This is when two queries in the same transaction, against the same table, use the same ‘WHERE’ clause, and the query executed last returns more rows than the first one. Only the serializable and snapshot isolation levels protect a transaction from phantom reads.

In order to solve the above mentioned concurrency issues, SQL Server uses the following type of locks.

As I have mentioned earlier, the type of lock which the SQL server will be acquired depends on the active transactions isolation level. I will briefly describe each isolation level a bit further.

Read Committed Isolation Level – This is the default isolation level for new connections in SQL Server. This makes sure that dirty reads do not occur in your transactions. If the connection uses this isolation level, and if it encounters a dirty row while executing a DML statement, it’ll wait until the transaction which owns that row has been committed or rolled back, before continuing execution further ahead.

Read Uncommitted Isolation level - Though this is not highly recommended by experts, it's better to consider about it too. It may result in a 'dirty read', but when correctly used it could provide great performance benefits.

You should consider using this isolation level only in routines where the issue of dirty reads is not a problem. Such routines usually return information that is not directly used as a basis for decisions. A typical example where dirty reads might be allowed is for queries that return data that are only used in lists in the application (such as a list of customers) or if the database is only used for read operations.

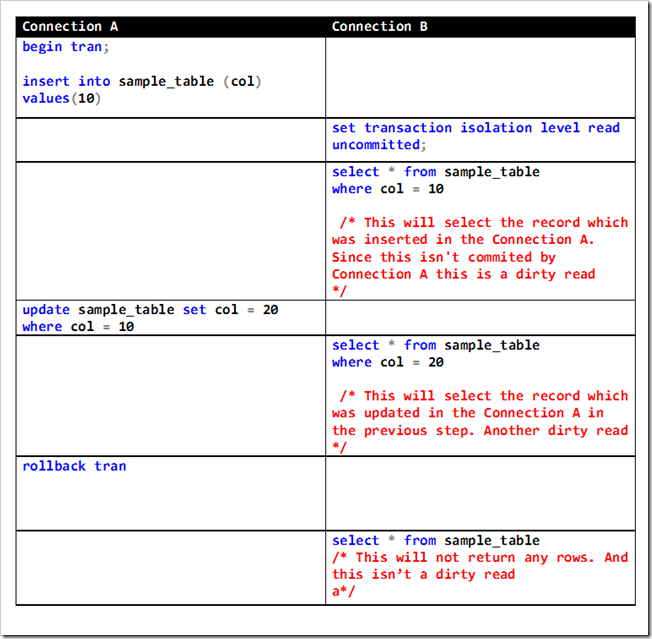

The read uncommitted isolation level is by far the best isolation level to use for performance, as it does not wait for other connections to complete their transactions when it wants to read data that these transactions have modified. In the read uncommitted isolation level, shared locks are not acquired for read operations; this is what makes dirty reads possible. This fact also reduces the work and memory required by the SQL Server lock manager. Because shared locks are not acquired, it is no problem to read resources locked by exclusive locks. However, while a query is executing in the read uncommitted isolation level, another type of lock called a ‘schema stability lock’ (Sch-S) is acquired to prevent Data Definition Language (DDL) statements from changing the table structure. Below is an example of the behavior of this isolation level.

Repeatable Read Isolation Level - In this isolation level, it guarantees that dirty reads do not happen in your transaction. Also it makes sure that if you execute/issue two DML statements against the same table with the same where clause, both queries will return the same results. But this isolation level will protect against updates and deletes of earlier accessed rows, but not the inserts, which is known as ‘Phantom’ rows concurrency problem. Note that phantom rows might also occur if you use aggregate functions, although it is not as easy to detect.

Serializable Isolation Level – This guarantees that none of the aforesaid concurrency issues can occur. It is very much similar to the ‘repeatable read isolation level’ except that this prevents the ‘phantom read’ also. But use of this isolation level increases the risk of having more blocked transactions and deadlocks compared to ‘Repeat Read’. However it will guarantee that if you issue two DML statements against the same table with the same WHERE clause, both of them will return exactly the same results, including same number of row count. To protect the transaction from inserts, SQL Server will need to lock a range of an index over a column that is included in the WHERE clause with shared locks. If such an index does not exist, SQL Server will need to lock the entire table.

Snapshot Isolation Level – In addition to the SQL’s standard isolation levels, SQL 2005 introduced ‘Snapshot Isolation Level’. This will protect against all the above mentioned concurrency issues, like the ‘Serializable Isolation Level’. But the main difference of this is, that it does not achieve this by preventing access to rows by other transaction. Only by storing versions of rows while the transaction is active as well as tracking when a specific row was inserted.

To illustrate this I will be using a test database. It’s name is ‘SampleDB’. First you have to enable the ‘Snapshot Isolation Level’ prior using it

Now we’ll create a sample table and insert few records.

Read Committed Snapshot Isolation Level – This can be considered as a new implementation of the ‘Read Committed’ isolation level. When this option is set, this provides statement level read consistency and we will see this using some examples in the post. Using this option, the reads do not take any page or row locks (only SCH-s: Schema Stability locks) and read the version of the data using row versioning by reading the data from tempdb. This option is set at the database level using the ALTER DATABASE command

I will illustrate the use of this isolation level with a sample. First enable the required isolation level.

Now lets create a table and populate it with few sample data.

Now open two query windows in SQL Server Management Studio.

Without committing execute the following in the second window

And you can see, even without committing, it’ll read from the older values, from the row versions which were created in the tempdb. If it was only the ‘Read Commited’ isolation level without the ‘Read Committed Snapshot’ option turned on, this select statement would have been locked.

Well both parties are correct up to a certain point. Actually lock durations are depend on the Isolation Levels.

As mentioned in the SQL-99 Standards, there are 4 Transaction Isolation Levels

- Read Committed (Default)

- Read Uncommitted

- Repeatable Read

- Serializable

- Snapshot

- Read Committed Snapshot

- Lost Update

- Dirty Read

- Non-Repeatable Read

- Phantom Reads

Lost Update – This can take place in two ways. First scenario: it can take place when data that has been updated by one transaction (Transaction A), overwritten by another transaction (Transaction B), before the Transaction A commits or rolls back. (But this type of lost update can never occur in SQL Server** under any transaction isolation level)

The second scenario is when one transaction (Transaction A) reads a record and retrieve the value into a local variable and that same record will be updated by another transaction (Transaction B). And later Transaction A will update the record using the value in the local variable. In this scenario the update done by Transaction B can be considered as a ‘Lost Update’.

Dirty Read – This is when the data which is changed by one transaction (Uncommitted) is accessed by a different transaction. All isolation levels except for the ‘Read Uncommitted’ are protected against ‘Dirty Reads’.

Non Repeatable Read – This is when a specific set of data which is accessed more than once in one transaction (Transaction A) and between these accesses, it’s being updated or deleted by another transaction (Transaction B). The repeatable read, serializable, and snapshot isolation levels protect a transaction from non-repeatable reads.

Phantom Read – This is when two queries in the same transaction, against the same table, use the same ‘WHERE’ clause, and the query executed last returns more rows than the first one. Only the serializable and snapshot isolation levels protect a transaction from phantom reads.

In order to solve the above mentioned concurrency issues, SQL Server uses the following type of locks.

- Shared or S-locks - Shared locks are sometimes referred to as read locks. There can be several shared locks on any resource (such as a row or a page) at any one time. Shared locks are compatible with other shared locks.

- Exclusive or X-locks - Exclusive locks are also referred to as write locks. Only one exclusive lock can exist on a resource at any time. Exclusive locks are not compatible with other locks, including shared locks.

- Update or U-locks - Update locks can be viewed as a combination of shared and exclusive locks. An update lock is used to lock rows when they are selected for update, before they are actually updated. Update locks are compatible with shared locks, but not with other update locks.

As I have mentioned earlier, the type of lock which the SQL server will be acquired depends on the active transactions isolation level. I will briefly describe each isolation level a bit further.

Read Committed Isolation Level – This is the default isolation level for new connections in SQL Server. This makes sure that dirty reads do not occur in your transactions. If the connection uses this isolation level, and if it encounters a dirty row while executing a DML statement, it’ll wait until the transaction which owns that row has been committed or rolled back, before continuing execution further ahead.

Read Uncommitted Isolation level - Though this is not highly recommended by experts, it's better to consider about it too. It may result in a 'dirty read', but when correctly used it could provide great performance benefits.

You should consider using this isolation level only in routines where the issue of dirty reads is not a problem. Such routines usually return information that is not directly used as a basis for decisions. A typical example where dirty reads might be allowed is for queries that return data that are only used in lists in the application (such as a list of customers) or if the database is only used for read operations.

The read uncommitted isolation level is by far the best isolation level to use for performance, as it does not wait for other connections to complete their transactions when it wants to read data that these transactions have modified. In the read uncommitted isolation level, shared locks are not acquired for read operations; this is what makes dirty reads possible. This fact also reduces the work and memory required by the SQL Server lock manager. Because shared locks are not acquired, it is no problem to read resources locked by exclusive locks. However, while a query is executing in the read uncommitted isolation level, another type of lock called a ‘schema stability lock’ (Sch-S) is acquired to prevent Data Definition Language (DDL) statements from changing the table structure. Below is an example of the behavior of this isolation level.

Repeatable Read Isolation Level - In this isolation level, it guarantees that dirty reads do not happen in your transaction. Also it makes sure that if you execute/issue two DML statements against the same table with the same where clause, both queries will return the same results. But this isolation level will protect against updates and deletes of earlier accessed rows, but not the inserts, which is known as ‘Phantom’ rows concurrency problem. Note that phantom rows might also occur if you use aggregate functions, although it is not as easy to detect.

Serializable Isolation Level – This guarantees that none of the aforesaid concurrency issues can occur. It is very much similar to the ‘repeatable read isolation level’ except that this prevents the ‘phantom read’ also. But use of this isolation level increases the risk of having more blocked transactions and deadlocks compared to ‘Repeat Read’. However it will guarantee that if you issue two DML statements against the same table with the same WHERE clause, both of them will return exactly the same results, including same number of row count. To protect the transaction from inserts, SQL Server will need to lock a range of an index over a column that is included in the WHERE clause with shared locks. If such an index does not exist, SQL Server will need to lock the entire table.

Snapshot Isolation Level – In addition to the SQL’s standard isolation levels, SQL 2005 introduced ‘Snapshot Isolation Level’. This will protect against all the above mentioned concurrency issues, like the ‘Serializable Isolation Level’. But the main difference of this is, that it does not achieve this by preventing access to rows by other transaction. Only by storing versions of rows while the transaction is active as well as tracking when a specific row was inserted.

To illustrate this I will be using a test database. It’s name is ‘SampleDB’. First you have to enable the ‘Snapshot Isolation Level’ prior using it

alter database SampleDB set allow_snapshot_isolation on; alter database SampleDB set read_committed_snapshot off;

Now we’ll create a sample table and insert few records.

create table SampleIsolaion( id int, name varchar(20), remarks varchar(20) default '' ) insert into SampleIsolaion (id,name,remarks) select 1, 'Value A', 'Def' union select 2, 'Value B', 'Def'

Read Committed Snapshot Isolation Level – This can be considered as a new implementation of the ‘Read Committed’ isolation level. When this option is set, this provides statement level read consistency and we will see this using some examples in the post. Using this option, the reads do not take any page or row locks (only SCH-s: Schema Stability locks) and read the version of the data using row versioning by reading the data from tempdb. This option is set at the database level using the ALTER DATABASE command

I will illustrate the use of this isolation level with a sample. First enable the required isolation level.

alter database SampleDB set read_committed_snapshot on; alter database SampleDB set allow_snapshot_isolation on;

Now lets create a table and populate it with few sample data.

create table sample_table( id int, descr varchar(20), remarks varchar(20) ) insert into sample_table select 1,'Val A','Def' union select 2,'Val B','Def'

Now open two query windows in SQL Server Management Studio.

--Window 1 begin tran update sample_table set descr = 'Val P', remarks = 'Window 1' where id = 1

Without committing execute the following in the second window

--Window 2 begin tran set transaction isolation level read committed select * from sample_table

And you can see, even without committing, it’ll read from the older values, from the row versions which were created in the tempdb. If it was only the ‘Read Commited’ isolation level without the ‘Read Committed Snapshot’ option turned on, this select statement would have been locked.

No comments :

Post a Comment